"I feel more strength now than ever before,

but this strength, this driving energy, shall be carefully bridled and directed with wisdom ... My ambition is everything — pleasure, physical sensations mean nothing compared to great accomplishments."

-- Bob Mizer in a letter to his mother, Delia Mizer, from a work farm in Saugus, California, May 28th, 1947.

The above quote was pulled from a series of letters written by American photographer Bob Mizer to his mother, following his arrest and subsequent imprisonment in the spring of 1947.

He spent a year at a work camp in Saugus, California (now part of Santa Clarita) after being wrongly accused of having sex with a model who was a minor, among other charges. But his career was catapulted into infamy in 1954 when he was convicted of the unlawful distribution of obscene material through the US mail. The material in question was a series of black and white photographs, taken by Mizer, of young bodybuilders wearing what were known as posing straps -- a precursor to the g-string. At the time, the mere suggestion of male nudity was not only frowned upon, but also illegal. Despite societal expectations and pressure from law enforcement, Mizer would go on to build a veritable empire on his beefcake photographs and films, with the establishment of the influential studio, the Athletic Model Guild.

Mizer's letters from Saugus, along with a handful of correspondence from a trip to Europe in the early 1950s, and his diaries, kept from the age of 14, make up the most comprehensive firsthand account of the long and complicated life of one of America's most unique and eccentric photographic voices. Perhaps the most informative portion of what remains of the Mizer estate, however, are a collection of photographs that have rarely been seen, even by those closest to the photographer. A series of these photographs appeared first Exile Gallery in Berlin in February 2010, in a first-of-its-kind exhibition entitled "Bob Mizer: Selected Private Works 1942-1992."

At the time of his death, Bob Mizer was probably best known for his groundbreaking magazine Physique Pictorial: a publication that mixed photographs and illustrations with Mizer's vitriolic political meanderings. In the span of his near 50-year career, he created a body of work that both reflected and skewed American ideals of masculinity, ranging from dramatic lit black and white photographs of musclemen to colorfully extreme close-ups of male genitalia. From his home in Los Angeles, he photographed thousands of men, ranging from Hollywood actors and bodybuilders to hustlers and porn stars. His portfolio, estimated at nearly one million different images and thousands of films and video taps, contains photographs of unique cultural figures, including action star and politician Arnold Schwarzenegger, Andy Warhol muse Joe Dallesandro, and contemporary artist Jack Pierson. The collection is now housed at the Bob Mizer Foundation in Northern California, however, following his death, a series of events unfolded that threatened to keep Mizer's work out of the public arena forever.

When Mizer died, his estate went to a man named Wayne Stanley, who worked at AMG for the last few years of its existence. For the next two years, Stanley attempted to keep Mizer's operation afloat, even taking photographs of popular AMG models himself, but the most important part of the business was missing -- Bob Mizer. In 1994, Stanley put the properties up for sale, sectioning it off into four parts. Eighteen months later, the final property was sold, and Stanley relocated to Alameda, CA. Mizer's black and white prints and negatives were kept in Stanley's garage, and his 35mm color work was stacked floor-to-ceiling in a nearby public storage unit. His films and videos remained in Los Angeles -- the films were sent to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, while the video tapes were stored on documentary filmmaker Marvin Jones' back porch. Back issues of Physique Pictorial changed hands a few times before landing in yet another storage unit.

In 2004, he made his final sale to the founder of the Bob Mizer Foundation, Dennis Bell, handing over all of the remaining photographs, including 35mm color slides, 4x5 black and white negatives, 2 1/4 color transparencies, and a card catalog that mapped out the collection in its entirety. Over time, Bell pieced the collection back together -- he was able to relocate and acquire all of Mizer's remaining films and video tapes, and most of the props, equipment, and backdrops John Sonsini had rescued from dumpsters more than 10 years earlier.

There is no real way of knowing what all was lost in the days and years following Mizer's death, but what remains of his estate paints a picture of a complicated and meticulous artist. He was a work horse. He shot obsessively, nearly everyday, often multiple models, even continuing to work as his body deteriorated from renal failure -- his last known session took place just two months before he died. Each photo was kept and scrutinized, some marked with the words "do not print," others accompanied by notes about lighting or exposure. Every last shot was filed away, be it overexposed, double exposed, or hardly exposed at all. Video of his sessions, kept almost religiously from the early 80s on, reveal an unusual process, with a stationary camcorder capturing every instant. Mizer can be heard coaching his models, flash units popping in the background.

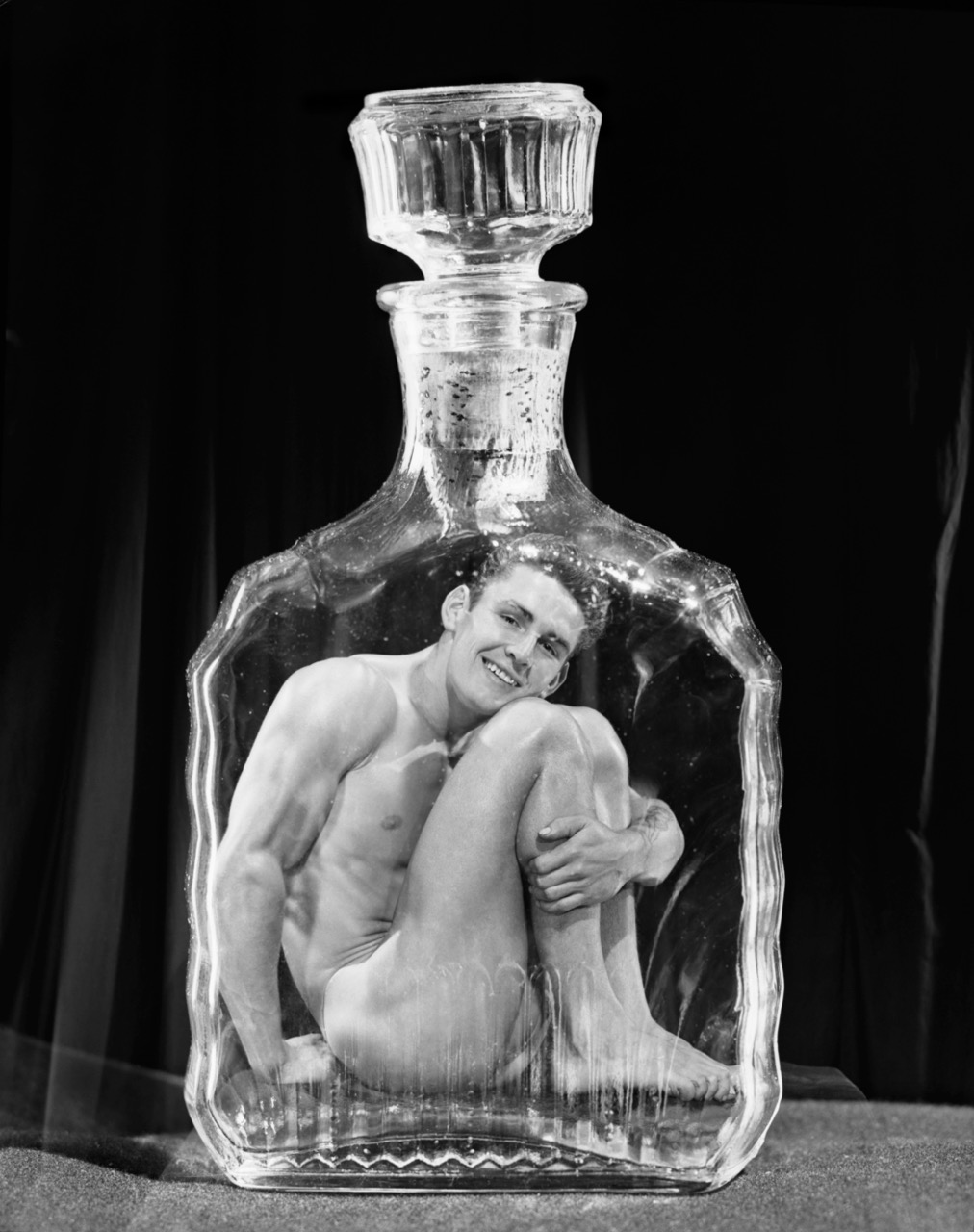

He was an extremely successful commercial photographer -- no small feat, considering his subject matter -- and he knew exactly what his customers wanted to see. Nonetheless, he steadily produced images that stand out from the standard beefcake that made him famous. In the cardboard boxes that housed his slides and negatives, right alongside the posing and preening, are images that Mizer himself never presented to the public, perhaps out of fear that they would be misunderstood. Even the many posthumous gallery exhibits and coffee table books overlook these, the most bizarre, and perhaps the most intriguing of his photographs.

He had a keen understanding of composition and lighting, from the beginning, and was an early adopter to new advances in photography -- his earliest color work dates back as far as the mid-1940s. The images, referred to here as his personal works, show all of these things while presenting a truly unique vision of masculine ideals. From his very earliest photographs, taken of friends and body-building competitions on Santa Monica's Muscle Beach, Mizer trained his lens on portrayals of masculinity, and as the years progressed, his work turned from standard representations -- bodybuilder, construction worker, sailor -- to multi-layered constructions. A black lumber jack, set against a desert sunset, sports a Gucci t-shirt and skin-tight jeans. A disheveled Jesus-figure, arm open-wide against a fabric-draped cross, stands, pelvis thrust forward, fully erect. Then there are the more traditional images: the unusual fashion photographs and colorful portraits that similarly have never appealed to fans of Mizer's muscle men.

These images present an entirely new man. In these examples he is neither restrained as in his early beefcake photographs, nor explicit as in his later work. He is seen here exhibiting that strength he once spoke of: the "driving energy ... carefully bridled and directed with wisdom." Bob Mizer has never been considered a great artist. Despite his obvious impact on visual culture, and proclamations of his influence from renowned art world figures like David Hockney, he has, until now, been relegated to the world of outsider art, camp, or kitsch. He may not have received the acclaim he is due, but then the real Bob Mizer, the multi-faceted photographer with a keen eye for color and composition and a truly unique vision of American masculinity, has yet to make his debut.

Bob Mizer Foundation Bulletin

Foundation events and projects, gallery exhibitions, and updates on the latest Physique Pictorial availability. Once or twice a month, privately.

Sign Up Today

stay up on what we're up to